I was chatting a few nights ago With friends about summer plans, she mentioned that her first priority is trying to find time to visit her mother who lives in a different country. I remember her recently taking a long trip for her mother’s birthday and asking her elderly parents if all was well. Yes, my friend explained, but after a long lockdown where no one was allowed to travel, she now desperately needs to see her mother more. And since her mother doesn’t want to move, my friend just has to do more long haul flights, even though she doesn’t like to travel a lot and has a busy life with work and raising her own kids in NYC. York, thousands of miles away.

I can understand this. My own mother lives only one train ride away, but over the past year I too have found myself increasingly compelled to visit her—even during those visits, with just a word from her. A casual comment can make me feel like an angry teenager again. As I got older, I was reminded more and more that she was getting old too, and while our relationship was challenging at times, I had an inner urge to spend more time with her. It got me thinking about how delicate and complex the relationship between parent and child is, and how it changes throughout a lifetime.

In David Hockney’s double portrait In “My Parents” (1977), the British artist painted a family scene that is imagined to reflect his views on core aspects of his parents’ personalities, and how he understood their relationship. The artist’s father is looking down at a magazine on his lap, and while his attention is clearly off the artist, the audience, and his wife sitting next to him, his attention is slightly off in the foreground of the canvas. His feet didn’t quite hit the ground, as if he was restless, impatient to be released. Despite the presence of family, this is a man completely immersed in his own world.

Hockney’s mother sits upright on the left side of the canvas, with her feet together on the floor and her hands folded in her lap, gazing intently at her son, the painter. Her expression is dutiful, and she seems to have gotten used to the role. A green sideboard on wheels stood between them. Its surface is a tray with a vase of flowers and a table mirror. In the reflection we can see a partial view of a small reproduction on the opposite wall, the painting The Baptism of Christ by Piero della Francesca. On the bottom shelf is a stack of books, including one about the 18th-century artist Jean-Siméon Chardin, known for his deceptively simple paintings of domestic scenes filled with emotional energy.

The photo shows a couple together in a way that has proven sustainable but can also be estranged, with hints of unspoken resentment or sadness. Hockney, born in 1937, painted this painting when he was 40 years old. But he began two years earlier with a portrait titled “My Parents and Myself,” which includes his own image in a mirror. He gave up the painting, much to the displeasure of both parents.

It made me wonder how Hockney would portray his parents when he was 20, when he was just a man, just learning to experience the ups and downs of adulthood—or at 60. For most of us, the way we view our parents, their relationship to each other and to us, changes as we go through our own life experiences.

When I was 31 or 32, I remember at that age my mother and I decided to take her and our lives in a new direction, eventually moving to a new country. I think about my mother and that situation completely differently than before. When we were kids, we believed our parents had all the power and limitless choices in the distant adult world they occupied. There is more empathy in my assessments now, because at that point I had experienced what it was like to be an adult who didn’t have full control over the circumstances of my life.

How do any of us paint a portrait of our own parents at this stage of our lives compared to when we were younger? What will we include? How will we account for how we imagine them in relation to ourselves?

The arrest job blew me away Melanie and I Swim (1978-79) by British painter Michael Andrews. The image shows a father teaching his young child to swim in a waist-deep river, based on photographs by the artist and his daughter. The father’s focus is on his baby, and he grabs her arm to steady her as she splashes her calf. With thick brown hair falling down her face, she smiled with a mixture of fear and delight. The water was so dark we could barely see what was below.

Melanie and I Swimmed (1978-79) by Michael Andrews © Tate/Tate Images

There are so many metaphors in this painting about how we spend our lives. Even though the child may stand at such a shallow depth, she still hopes that her father will guide her, just as she will in the future when she is far from solid ground. But she may not always have that support. Sometimes she will have to rely on herself. It’s a swimming lesson, but it’s also a survival lesson.

What makes this image so terrifying and moving, however, is how it speaks to another brave aspect of parenting. Time and time again, you must unleash your children into unknown worlds where you simply have no means or control to protect them. This can happen at any time in a child’s life, including adult children who may still need active support and parenting due to developmental issues or life choices. Some parents confront this fear on a more consistent basis because of how the world is socialized to see and treat children who look like them.

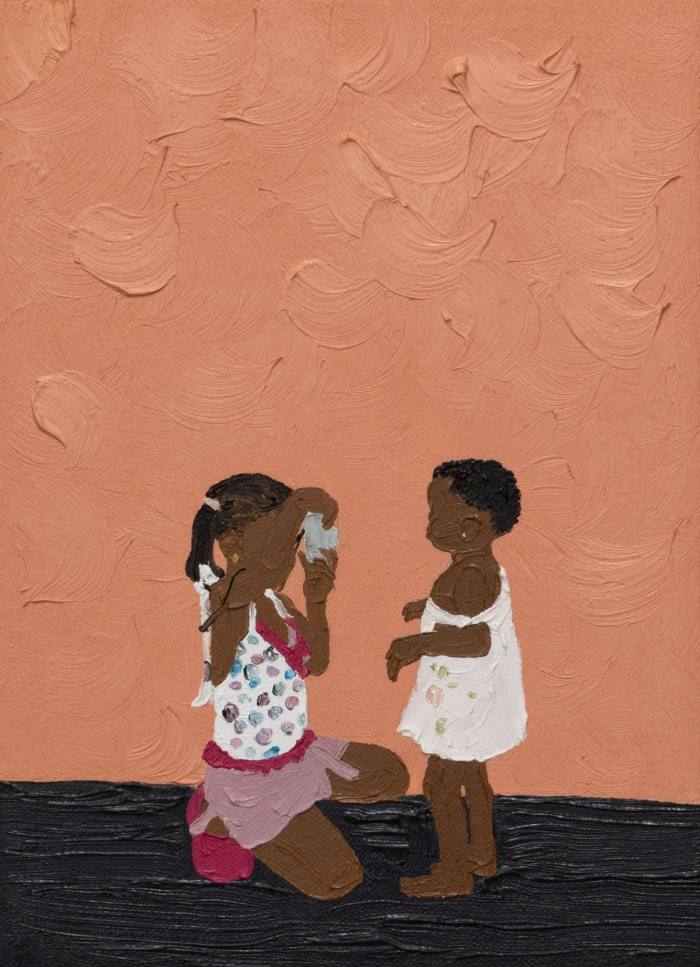

“Smile II” by Shaina McCoy, A 30-year-old Minneapolis-based artist, it’s a tiny 5″ x 7″ painting, but as I walked past her current exhibit in New York, I was immediately drawn to it, gaze. Two little girls face to face. One child wore a colorful polka-dot tank top and lavender shorts, her braided hair held in place with pink barrettes. She holds the camera up to her eyes and kneels in front of another child, a toddler in a white shift dress falling off one shoulder, who is taking her picture.

“Smile II” by Shaina McCoy (2023) © Jenny Gorman

McCoy doesn’t paint faces on her characters, but we still get a sense of the intimate scenes of the game and life training. There’s something beautiful about this moment where both kids are watching and being watched. The mutual gaze is an acknowledgment of belonging, safety, and worth, enough to be gazed with interest and care.

There are no parents in this painting, but parenthood is suggested by the careful way the child dresses, the camera she is taught to use, and the toddler she knows to care for even when they are playing. We can imply that someone communicated to the little photographer something about self-worth, about finding beauty in her and her sister’s faces, and about taking time to observe another human being.

But there is also some poignancy and pain about parenting in this picture. It feels like no matter how we raise our kids to value themselves or appreciate the good in the world, the world won’t always return the same loving gaze. This is true for many parents, but even more so for many parents of black children—especially in America, where the news regularly reminds us that we live in a society that doesn’t always respect our children. See them or train them to see themselves.

I love the fact that McCoy keeps her characters faceless. Discipline is the imagining of seeing any child as valuable and being able to provide care to them no matter what they look like or who they belong to.

The painting also made me think about the fact that we are all someone’s children. In some ways we still carry with us who we were as children, the way we were taught in this world, and the lessons we learned from our parents, for better or worse, as we find our own parents as adults self.

What we do with these teachings and lessons is parenting that we all must learn to do to ourselves. Sometimes that means re-examining how we were raised and recognizing which lessons we learned from our parents are pulling us away from life-giving patterns and relationships. Sometimes that means remembering and reclaiming powerful and positive teachings that remind us of who we can be in this world, no matter what the world suggests or demands of us.

Follow Enuma on Twitter @EnumaOkoro or email her enuma.okoro@ft.com

follow @ftweekend Be the first to hear about our latest stories on Twitter