A German start-up has secured initial funding to develop a revolutionary fusion energy machine it hopes will provide an abundant, emission-free source of electricity for the future.

Proxima Fusion was launched in January to build a complex device called a stellarator, and is the latest company to join the burgeoning fusion industry to generate electricity through fusion of atoms.

Although the funding amount is small, at only €7 million, it is significant because Proxima is the first fusion company to be spun out of Germany’s renowned Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics.

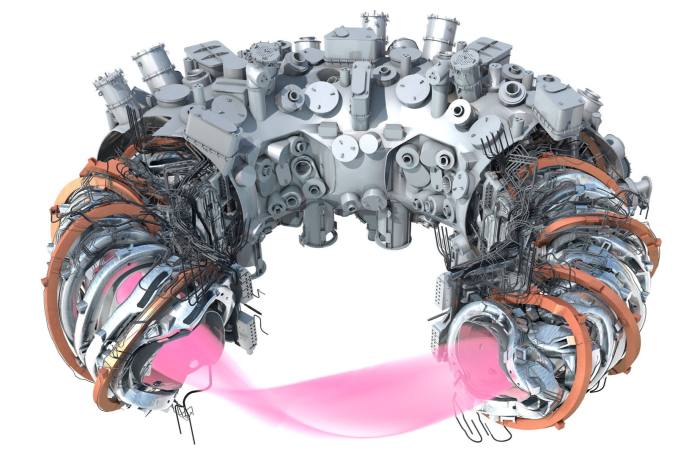

The institute is home to the world’s most advanced existing stellarator in Greifswald, eastern Germany, built over the past 27 years by government-funded scientists using supercomputers and advanced engineering.

Little known outside the plasma physics community, stellarators are an alternative to the better-known tokamak devices pioneered by Soviet scientists in the 1950s.

Both use giant magnets to levitate a floating plasma of hydrogen as it is heated to extreme temperatures, so nuclei fuse to release energy.

Until recently, nearly all the money spent on so-called magnetic confinement fusion was spent on tokamaks, such as the Joint European Torus facility in Oxford, England, or the Sparc facility built by Bill Gates-backed Commonwealth Fusion Systems in Massachusetts. .

The stellarator’s twisted structure is more complex to design and build than a traditional tokamak, but produces a more stable plasma, allowing scientists to sustain fusion reactions for longer periods of time.

“A tokamak is kind of easy to design, but hard to operate, and a stellarator is very difficult to design, but once you design it, it’s a lot easier to operate,” said Ian Hogarth, co-founder of the Plural Platform, which is collaborating with UVC in Germany. Partners co-led the €7 million investment.

Despite the achievements of Wendelstein 7-X, Thomas Klinger, Director of the Greifswald Division of the Max Planck Institute, says there is still a long way to go from there to commercial electricity © MPI for Plasma Physics

The stellarator was conceived by American physicist Lyman Spitzer in 1951, but largely abandoned after breakthroughs in the tokamak in the 1960s seemed to offer an easier route to fusion. Germany is one of the few countries that persists in stellarator research, starting research on Wendelstein 7-X at the Max Planck Institute in 1996, at a total cost to date of 1.3 billion euros.

“In building machines, we learn how to build machines,” Thomas Klinger, director of the institute’s Greifswald division since 2001, told the Financial Times. He added that the final design was the product of “long and tedious research”.

The W 7-X was first used by then-Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2016, and the machine has since made a series of scientific breakthroughs.

“They basically did the impossible,” Hogarth said. “With computing resources in the 1990s, they managed to design a stellarator . . . and now it sets records that basically define the entire field of magnetic confinement fusion.”

The close relationship between Proxima and the Max Planck Institute has prompted comparisons to Commonwealth Fusion, which spun out of MIT in 2018 and has since raised a record $2 billion from investors. Dollar.

“We have an affiliation with an institution that has more people (in plasma physics) than MIT,” said Proxima CEO Francesco Sciortino, who worked at the Max Planck Institute before founding the company. Work. “The question is, can we execute the same and really make it European champions?”

Despite the W 7-X’s achievements, Klinger said it was a long way from there to commercial force, which he warned could be another 25 years away.

While advances in materials science and an influx of private investment have raised hopes that abundant emissions-free fusion energy could be integrated into the grid by the 2030s, fusion machines have yet to produce more energy than the system itself consumes.

Four fusion investments have been made by Philippe Larochelle of Bill Gates Breakthrough Energy Ventures, who backed Commonwealth Fusion’s tokamak and the stellarator concept being developed by Type One in the US.

“The idea of fusion is that the prize is so big it’s worth multiple shots,” he said.