A truck driver takes this June 8, 2023 photo of the Fenix Marine Services rail terminal.

The “sluggish” pace of the International Terminal and Warehouse Alliance workforce at West Coast ports has slowed productivity at surface ports. As a result, MarineTraffic data showed what it called a “significant surge” in the average number of containers waiting outside port limits.

At the Port of Oakland, the average TEU (tonnary equivalent unit) waiting for port restrictions rose from 25,266 to 35,153 during the week of June 5, according to data from Supply Chain Intelligence. At the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, Calif., the average TEU waiting for port restrictions rose to 51,228 from 21,297 the previous week, a MarineTraffic spokesman said.

The total value of the 86,381 containers floating in the ports of Oakland, Los Angeles and Long Beach came to $5.2 billion, based on a value of $61,000 per container and customs data.

Seven-day rates for containers cleared through the Port of Oakland are 58 percent; at the Port of Long Beach, it’s 64 percent; and at the Port of Los Angeles, it’s 62 percent, according to data pulled exclusively for CNBC by Vizion, which tracks container movement. “Our data shows that ships will continue to arrive at West Coast ports and unload significant volumes of cargo over the next few days,” Vizion Chief Executive Kyle Henderson said. He said there is currently no indication that ocean carriers plan to cancel any sailings to those ports, but added, “If these labor disputes continue to affect port efficiency, we could see a backlog similar to what we saw during the pandemic. Obviously, this Is the last thing any shipper wants as we move into the second half of the year and peak season.”

A logistics manager who is aware of the way unionized rank-and-file workers’ dissatisfaction with unresolved issues in negotiations with port management is affecting work shifts told CNBC that the slowdown can be attributed to skilled workers not showing up for work. CNBC has also learned that at some port terminals, additional work requests through official work orders are not hanging on union hall walls for fulfillment. The Pacific Maritime Association, which negotiates on behalf of the port, was not allowed into the union hall to see if the dock order was indeed being requested. If additional job postings were posted, the data would show those job postings were not filled, CNBC has learned. Fill only with raw labor ordered from PMA.

Between June 2 and June 7, the ILWUs at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach refused to send lashing crews to secure cargo for transpacific voyages and untie cargo upon arrival, the PMA said in a statement Friday afternoon. . “Without this vital function, vessels sit idle, unable to load and unload, preventing U.S. export cargo at docks from reaching their destination,” the statement read. “The ILWU’s refusal to send the flagellants is part of a broader effort to stop a necessary workforce at the docks.”

Failure to fill 260 of the 900 jobs ordered at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach on Wednesday morning, a total of 559 registered dockworkers who came to the dispatch hall were denied jobs by the union, PMA said in a statement. statement.

“Every shift without lashers working results in more ships being idled, taking up berths and causing back-ups for incoming ships,” it said.

However, the ILWU’s decision to stop withholding labor has allowed terminals at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to temporarily avoid “a domino effect not seen since the collapse of supply chains last year,” PMA said.

PMA said operations at the ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach and Oakland had “generally improved,” but operations at the ports of Seattle and Tacoma had “slowed significantly.”

ILWU declined to comment, citing a media blackout during ongoing labor talks.

Truck and container backup

Average truck turns to and from West Coast ports rose.

A truck driver waiting for containers at the Fenix Marine Services terminal in Los Angeles shared photos with CNBC of their trucks, showing congestion on railroads and highways as truckers wait to pick up their containers.

Shippers are increasingly concerned about the potential need to find alternative supply chain options.

A spokesman for Long Beach, Calif.-based Cargomatic, which specializes in haulage and short-haul freight logistics, said it has not seen trade diversion yet, but added, “As a national haulage partner, we have contingency plans in place for capacity readiness. The good news is that serving our customers anywhere in the U.S. We know shippers are very nervous and if this continues, it’s only a matter of time before they change course.”

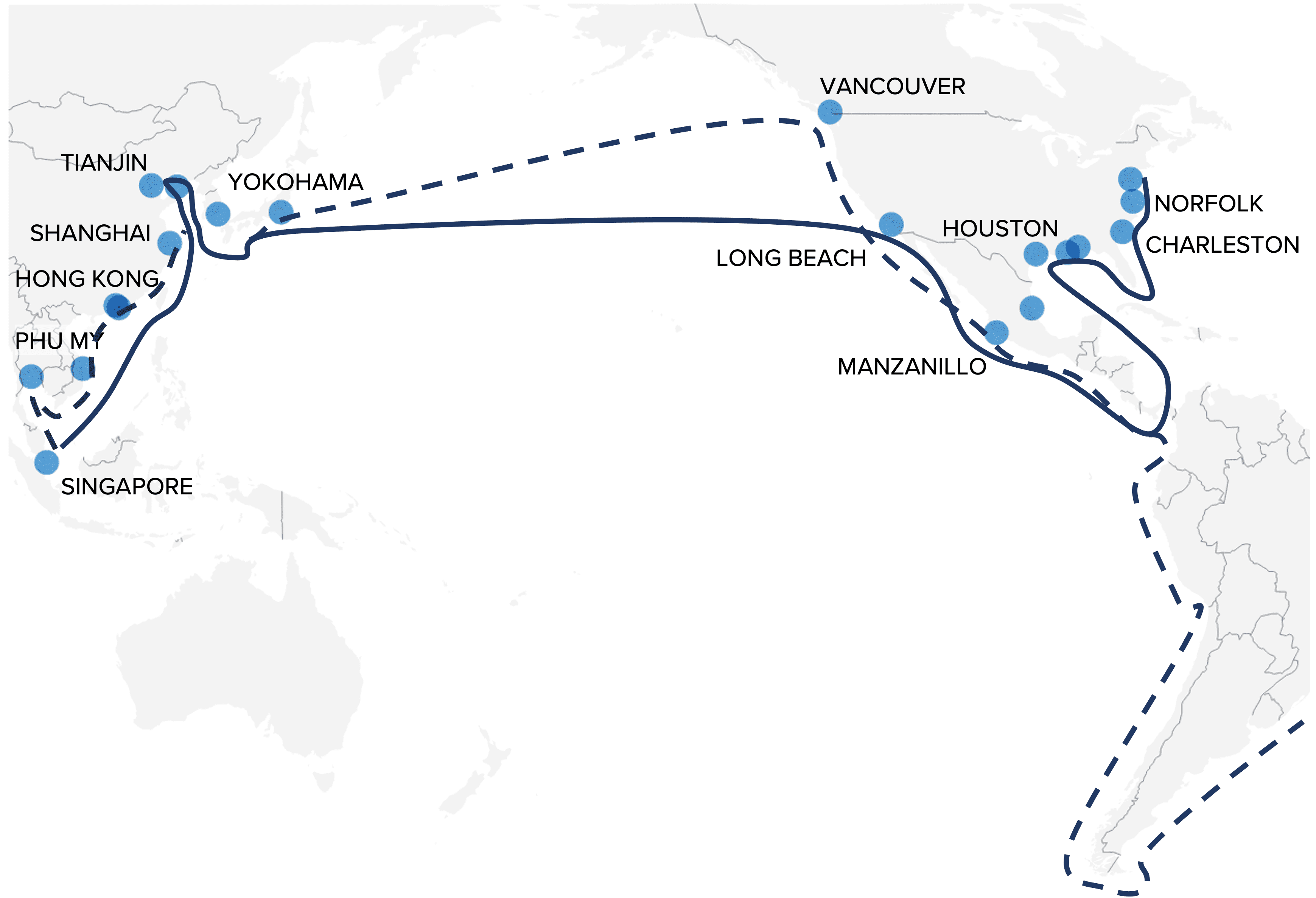

In its statement, the PMA said that despite improvements in some port operations, “repeated disruptive work actions by the ILWU at strategic West Coast ports have increasingly resulted in companies shifting cargo to more customer-friendly and reliable locations in the Gulf of Mexico and East Coast.” Place”

West coast ports have begun to restore throughput in recent months after slashing throughput at east coast ports over the past year due to volatility in labor contract negotiations.

A photo of a truck parked at the Fenix Marine Services terminal in the Port of Los Angeles, waiting to pick up a container the truck driver has taken.

Maritime intelligence firm Xeneta said its data showed container spot rates rose 15% in the first few days of June due to multiple simultaneous outages. The recent low water levels in the Panama Canal have limited cargo throughput, and shortly thereafter most ports on the West Coast of the United States stopped handling incoming and outgoing container trade.

“Shippers looking for a more reliable and resilient supply chain are now considering their options,” said Peter Sand, principal analyst at Xeneta. “He said.

Supply chain disruptions pile up waiting ships off West Coast amid Covid Affects trade shifts to Gulf and East Coast ports. If ships do start diverting again, there will be additional costs for diverted cargo, which will be borne by the shipper. If ships are diverted to a Gulf of Mexico or East Coast port, they must use the Panama Canal, with a surcharge on top of normal surcharges, as the Panama Canal is in a critical condition with low water levels and drought.

Monthly long-term “tramp” service from Asia to the Americas

— core trade routes — alternate route

Water problems at the Panama Canal exacerbate the costs of any trade diversion. It imposed weight requirements on ships – they needed to be lighter to pass. If the vessel meets or falls below this weight requirement, the shipper will pay an additional fee. Some ocean carriers, such as Hapag-Lloyd, charge a $260 container fee for shipping through the canal, in addition to the canal fee. CMA CGM charges $300 per container. If ships are heavier than current requirements, they will be forced to cross the Pacific Ocean and round the Horn of South America, adding weeks to travel time and travel costs.

“Ship diversions are some of the most difficult activities that shippers and our customers deal with during a crisis,” said Paul Brashier, vice president, Haulage and Intermodal, ITS Logistics. During the pandemic and its aftermath, a container bound for Los Angeles or Long Beach would show up in Houston or Savannah with little notice, he said. “We have visibility apps that alert us before containers arrive so we can reallocate trucking capacity at new ports. But if you don’t have that visibility, if you can’t track containers in real time like that, you’re not adapting.” With these changes, each container could face thousands of dollars in shipping and D&D costs. This inflationary pressure is having an adverse impact not only on shippers but also on consumers of these cargoes,” he added.

ITS Logistics raised its freight rail alert level to “red” this week, indicating a serious risk.

Supply chain costs have dropped significantly Globally, according to the Federal Reserve, although Fed Chairman Jerome Powell mentioned them as triggers of inflation beyond the control of the central bank. In a report by Jonathan Ostry, an economist at Georgetown University, soaring transportation costs lead to an increase in inflation of more than two percentage points in 2022.

“These slowdowns have left few options for shippers of containers already heading to the West Coast,” said Captain Adil Ashiq, head of MarineTraffic North America, who told CNBC earlier this week that supply chain issues at sea are “breaking the norm.”

“They can skip one port and go to another West Coast port, but they all experience some level of congestion,” he said on Friday. “So are they waiting or moving to Houston as the next closest port of discharge?”

If ships do decide to change course, it will add days to their journey, which will further delay the arrival of the product.

For example, if an incoming ship from Asia decides to divert to Houston, it adds 7-11 days to the Panama Canal. If the boat is allowed to pass through the canal, it will add 8-10 hours to the transit time. “Once you leave the canal and go to port, you have to add travel time. So we conservatively consider that if a ship decides to go directly from the canal to Houston, there will be an additional delay of 12-18 days. Even more, if you have to travel around South America ,”He said.

Key sectors of the U.S. economy have been pleading with the Biden administration to step in and broker a labor deal, including trade groups in retail and manufacturing. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce also joined the effort on Friday, expressing concern about a “severe shutdown” at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach that could cost the U.S. economy nearly $5 billion a day. Estimates suggest that broader strikes on the West Coast could cost about $1 billion a day.

“The best outcome is a voluntary agreement between the negotiating parties. But we fear that the current sticking point — the impasse over wages and benefits — will not be resolved,” its chief executive, Suzanne Clarke, wrote in a letter to President Biden.