by Taskeen Bhat

Expanding marketing efforts, both nationally and internationally, is critical. Effective promotion of authentic Kashmiri pashmina through strategic advertising and management can distinguish it from the mass-produced imitations that flood the market.

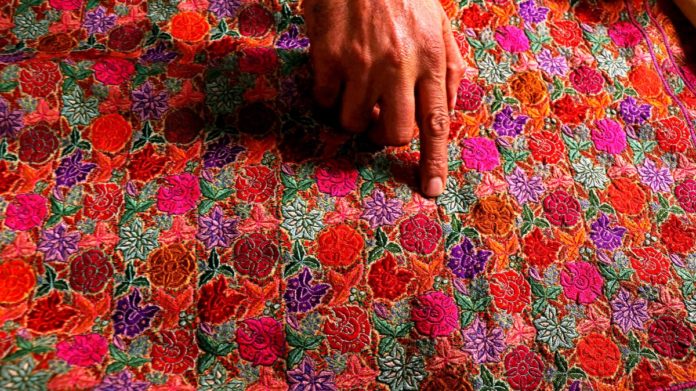

Within the soft, luxurious weave of a pashmina shawl lies a history that far surpasses the delicacy of its fibres. For centuries, the Kashmiri pashmina has been esteemed as a symbol of refinement and wealth, adorning the shoulders of European aristocrats and royal courts alike. This fabric, woven from the fine undercoat of Himalayan goats, bears the collective memory of Kashmir: its cultural exchange, the resilience of its artisans, and its role in global trade.

Kashmiri artisans have every reason to take immense pride in their craft, knowing that no colonial or external power has ever managed to alter its fundamental essence. British colonialism impacted the Pashmina shawl industry, primarily through its control of trade routes and influence over market demand. Yet the heart of this art form remained resolutely untouched.

Unlike numerous other cultural crafts hijacked or significantly altered during colonial rule, the labour-intensive skill of hand-weaving and embroidering pashmina shawls remained firmly in the hands of Kashmiri artisans. The introduction of jacquard looms, which flooded markets with imitation pashmina shawls, failed to replicate the artistry and fineness of the genuine article.

The craftsmanship of authentic Kashmiri pashmina shawls, woven with precision by hand, remains unrivalled by machine-made counterparts. Mass-produced alternatives may have offered a cheaper option, but they fell far short of the elegance and skill embedded in authentic pieces.

Each Kashmiri pashmina shawl embodies generations of knowledge, an artistry that lies beyond the capabilities of machines, and as such, it stands as a timeless testament to Kashmir’s cultural heritage.

At its peak, the pashmina industry formed the backbone of Kashmir’s economy, with only agriculture surpassing it in importance. There was a period when numerous families depended on this craft for their livelihood. Even today, it retains the potential to drive economic growth.

If given the necessary support, this industry could still prove a potent force in combating poverty and empowering Kashmiri women, who constitute a substantial proportion of the artisan workforce.

The pashmina industry remains largely unorganized. Bringing structure and support to this sector could become the cornerstone of its revival. Organizing the industry would ensure fair wages, better working conditions, and sustainable practices that directly benefit the artisans.

To safeguard this industry, immediate and decisive action is necessary. The 1985 Handloom Protection Act prohibits the industrial processing of pashmina fibre, intending to preserve the authenticity and traditional craftsmanship of pashmina production. Although the act plays a crucial role in safeguarding the integrity of pashmina, enforcement poses a significant challenge, particularly as demand for more affordable alternatives continues to rise.

Supporting and protecting spinners is a pressing priority. Traditionally, spinning pashmina wool has been a craft dominated by Kashmiri women. However, the rise of electric spinning machines, coupled with insufficient wages, has led many of these skilled women to abandon the profession.

In recent years, there has been a rise in pashmina shawls being woven on power looms, which further complicates efforts to preserve traditional handloom methods. Despite legal protection, the market remains saturated with mass-produced imitations manufactured in industrial factories, often using synthetic fibres or lower-quality wool blends. These counterfeit products devalue genuine Kashmiri pashmina, making it difficult for traditional artisans to compete with cheaper, machine-made alternatives.

Expanding marketing efforts, both nationally and internationally, is critical. Effective promotion of authentic Kashmiri pashmina through strategic advertising and management can distinguish it from the mass-produced imitations that flood the market.

Connecting with rural artisans, particularly those in remote areas, is another essential step. Technology can bridge the gaps that isolate these craftsmen, integrating them into the broader market and providing access to resources and buyers previously out of reach.

There is also a growing need to support new business entrepreneurs venturing into the pashmina industry. These individuals bring fresh perspectives and innovations that can drive growth and creativity. Encouraging their participation through start-up incentives, mentorship programmes, and access to business development resources will revitalise the sector and ensure its long-term sustainability.

Integrating environmental consciousness into the industry’s revival is essential. Promoting sustainable practices – such as the use of eco-friendly dyes, efficient washing techniques, and waste reduction – aligns with global trends towards environmental responsibility.

The government has a pivotal role to play in making natural dyes more affordable and accessible, thereby supporting artisans in adopting greener methods and producing higher-quality shawls. Innovative programmes that bridge traditional craftsmanship with modern economic strategies can have a significant impact.

For example, a comprehensive artisan support scheme could provide financial assistance, training, and resources to spinners and weavers. Such a scheme might include subsidies for raw materials, grants for upgrading tools and infrastructure, and marketing support to connect artisans with global markets.

Furthermore, the establishment of pashmina craft hubs could serve as centres of excellence. These hubs would provide artisans with technical training and access to advanced weaving techniques while conserving traditional methods. They could also facilitate partnerships with design institutions, creating opportunities for artisans to showcase their work in international fashion arenas.

As a researcher, I firmly believe that regional institutions have a crucial role to play in conservation efforts, thanks to their localized knowledge and personal stake in preserving their heritage and environment. Their close ties to the community, culture, and ecosystems they inhabit enable them to develop targeted strategies that are both culturally and ecologically appropriate.

It is heartening to note the contribution of institutions such as NIFT Srinagar to this mission, particularly through their focus on textile practices. By combining traditional techniques with contemporary methods, NIFT Srinagar illustrates how regional institutions can effectively bridge heritage and innovation, supporting a more sustainable future.

Partnerships with such higher educational institutions can foster innovation and introduce modern business practices. Integrating craft studies and museum spaces within higher academic institutions can inspire a new generation to appreciate and engage with arts and crafts, cultivating interest in conserving their heritage.

(The author has a PhD from Christ University Bangalore. Ideas are personal.)