by Dr Nawab John Dar

Scientist, SALK Institute of Biological Sciences, San Diego, California, USA

“In 2024, the world is urged to act-dementia is not a natural part of ageing, and it’s time we all recognize that. With the theme ‘Time to act on dementia, Time to act on Alzheimer’s,’ this year’s campaign challenges outdated perceptions and calls for a global commitment to dismantle stigma. Alzheimer’s disease, a devastating condition that erodes memory and thinking skills, is becoming a growing concern in India as life expectancy rises, impacting more families. Unfortunately, many still mistake early signs for normal ageing, delaying crucial treatment, especially in rural areas where mental health stigma persists. However, with new research, improved caregiver support, and awareness efforts, there is hope to reshape how Alzheimer’s is understood and managed in India. World Alzheimer’s Day emphasises the power of collective action in reshaping the future of care and understanding”

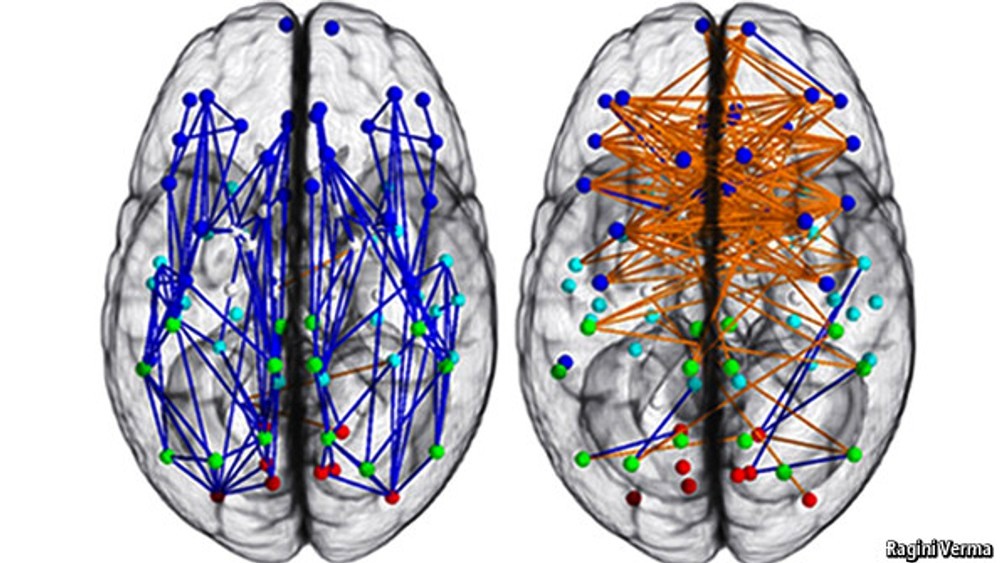

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurological disorder that gradually erodes memory, thinking skills, and the ability to perform everyday tasks, affecting millions worldwide. As the leading cause of dementia worldwide, it accounts for 60-80% of all dementia cases, affecting millions globally. First identified by Dr Alois Alzheimer in 1906, this once little-known condition has now become a major health crisis, particularly as ageing populations face a higher risk. With its slow but relentless progression, Alzheimer’s is not just a medical issue but a profound social and emotional challenge for families and caregivers alike. At its core, Alzheimer’s disease is marked by the abnormal accumulation of two types of proteins in the brain: beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These harmful protein deposits interfere with communication between brain cells, leading to their degeneration and eventual death. As neurons die, the brain shrinks, and the individual begins to experience significant memory loss, confusion, and a decline in cognitive functions that progressively worsen over time.

In many cases, the onset of AD is preceded by a stage known as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). MCI serves as a transitional phase where individuals begin to notice cognitive decline, particularly in memory but are still able to manage daily activities. Importantly, MCI does not always lead to Alzheimer’s; around 10-15% of people with MCI progress to AD each year. However, this phase offers a critical window for early intervention and monitoring, as those diagnosed with MCI are at increased risk of developing the disease.

The causes of Alzheimer’s disease are complex and still not fully understood. However, ageing remains the most significant risk factor, with the likelihood of developing AD doubling every five years after the age of 65. Genetics also plays a role, particularly for those with early-onset Alzheimer’s, which occurs before age 65. One of the most notable genetic risk factors is the presence of the apolipoprotein E (APOE)ε4 allele, which increases both the risk of developing the disease and its early onset. Yet, not all risk is inherited-lifestyle choices and health conditions also play a major part in determining who may develop the disease. Studies have identified several modifiable risk factors that could significantly reduce the risk of AD. These include maintaining good cardiovascular health, as conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and obesity have been linked to cognitive decline. Education, social engagement, and physical activity also play protective roles. A 2020 report by the Lancet Commission estimated that up to 40% of dementia cases could be prevented or delayed by addressing such factors. This highlights the importance of lifestyle in managing brain health, as well as the urgent need for public awareness campaigns to promote preventive measures.

India, like many countries with rapidly ageing populations, is witnessing an alarming rise in Alzheimer’s cases. The Dementia India Report 2020, published by the Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India (ARDSI), estimated that 5.3 million people were living with dementia in India as of 2020—a figure expected to surge to 7.6 million by 2030 and 14 million by 2050. This rapid increase presents serious challenges for the nation’s healthcare infrastructure, especially in regions with limited facilities, such as Kashmir. Like many rural areas across India, Kashmir faces significant barriers to early diagnosis and treatment due to stigma, low awareness, and misconceptions about dementia. Access to specialized care is also limited, making it harder for families to get the support they need.

However, some unique aspects of Kashmiri culture, like in other Indian society at large, may offer protection against cognitive decline. The strong family support systems, essential for emotional and practical care, play a crucial role in managing Alzheimer’s. Additionally, the traditional practices of Kashmiri society, including religious activities and mindfulness practices, may have cognitive benefits, helping improve mental well-being and possibly slowing dementia progression. Emerging research suggests that certain elements of the Indian diet, such as turmeric, known for its compound curcumin, may have neuroprotective effects. Curcumin possesses anti-inflammatory properties and might reduce the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques in the brain. While these findings are promising, further research is needed to confirm whether turmeric can play a role in preventing or treating Alzheimer’s disease.

Current Scenarios

The global burden of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has become a critical health concern, with over 55 million people worldwide living with dementia, and nearly 10 million new cases are diagnosed each year. Projections indicate this number will triple by 2050, driven largely by ageing populations and increasing life expectancy. This surge comes with a significant economic impact, in 2019, the global societal costs of dementia were estimated at US $1313.4 billion, which is US $23,796 per person with dementia. The global economic burden of dementia is projected to increase to $4.7 trillion in 2030, $8.5 trillion in 2040, and $16.9 trillion in 2050. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are expected to account for 65% of the global economic burden in 2050. The annual cost of dementia care in India varies depending on the severity of the disease and location. In urban areas, the cost ranges from INR 45,600 to INR 2,02,450, while in rural areas it ranges from INR 20,300 to INR 66,025. Dementia is estimated to cost India around $13 billion annually in lost productivity and healthcare costs. The annual household cost of dementia is estimated to be $571, which is 20% of the annual healthcare spending by the Indian government.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains a significant global challenge, and the situation in India is particularly complex due to various socio-economic and healthcare-related factors. Alzheimer’s is typically diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluations, cognitive assessments, and imaging, yet several challenges and limitations impact the accuracy of these diagnoses, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Global Diagnostic Practices

The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease begins with a comprehensive assessment of medical history, focusing on cognitive decline, behavioural changes, and any family history of dementia, followed by a physical examination to exclude other causes of memory issues, such as cardiovascular disease or depression. Cognitive and neuropsychological tests, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), are used to evaluate memory, attention, problem-solving, and language abilities, identifying patterns indicative of Alzheimer’s. Neurological examinations assess motor functions, reflexes, and coordination to rule out other neurological disorders like Parkinson’s disease or stroke. Brain imaging techniques, such as MRI or CT scans, are employed to detect brain atrophy or structural changes, like hippocampal shrinkage, and exclude other conditions such as tumours or vascular issues. Blood and laboratory tests help rule out conditions that may mimic Alzheimer’s, including vitamin deficiencies, thyroid dysfunction, or infections. Recently, advancements in biomarkers like amyloid-beta and tau proteins, detectable through cerebrospinal fluid analysis or PET scans, offer promising early diagnostic potential, though their use is limited by cost and availability.

India: Practices and Challenges

In India, the diagnostic process for Alzheimer’s largely mirrors global practices, but several factors, including healthcare accessibility, cultural beliefs, and resource constraints, significantly affect the accuracy and timeliness of diagnosis. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease begins with a detailed medical history and family interviews, but cultural factors often lead to early symptoms such as forgetfulness or confusion being dismissed as normal ageing. This cultural stigma and lack of awareness may delay seeking medical attention. Cognitive and neuropsychological tests like the MMSE and MoCA are used, but language barriers and low literacy rates complicate their effectiveness, particularly in rural and underserved areas where adaptation to local languages and contexts is often lacking. Neurological examinations are performed, but access to neurologists and specialized care is limited, especially in rural regions, leading to potential misdiagnoses by general practitioners. Advanced imaging techniques such as MRI and CT scans are primarily available in urban hospitals or private facilities, with rural patients often lacking access due to financial constraints. Even when available, early-stage Alzheimer’s may not show visible changes on these scans. Blood tests are conducted to rule out conditions that may mimic cognitive decline, but comprehensive lab work is not always accessible in resource-limited settings, increasing the risk of misdiagnosis. While biomarkers like amyloid-beta and tau hold promise for early detection in developed countries, their use in India is limited by high costs and inadequate infrastructure, resulting in a reliance on traditional diagnostic methods that may miss early-stage Alzheimer’s.

Factors Affecting Diagnosis

Early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, such as memory loss and confusion—are frequently attributed to normal ageing or stress, often due to cultural perceptions. This leads to many patients delaying medical consultations until the disease has significantly advanced, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Specialized care, including neurologists and memory clinics, is predominantly available only in urban centres, leaving rural areas with limited access to these crucial resources. The high cost of specialized care and diagnostic procedures, like MRIs and PET scans, can be prohibitive for many patients, further delaying diagnosis. Cultural stigma surrounding cognitive and mental health issues exacerbates the problem, as families may fear social judgment or remain unaware of the disease’s severity, hindering early intervention. Moreover, cognitive testing tools are often not adapted to local languages or cultural contexts, which can lead to misinterpretation of results, especially among populations with lower literacy levels. Economic barriers and a lack of awareness and training among healthcare providers, particularly in primary care settings, contribute to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. Additionally, overlapping conditions such as vascular dementia, depression, and other neurodegenerative diseases can present with similar symptoms, making accurate diagnosis even more challenging without advanced diagnostic tools.

Treatment: Current Approaches and Challenges

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and treatment efforts focus on slowing disease progression, managing symptoms, and enhancing the quality of life for both patients and caregivers. Alzheimer’s treatment involves a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, though each approach faces limitations.

Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, are commonly prescribed for managing mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD). These medications work by increasing levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter essential for memory and learning, through the inhibition of the enzyme responsible for breaking it down. While these drugs can temporarily slow cognitive decline and improve daily functioning, their benefits are modest, and they do not halt or reverse the disease’s progression; their effects may diminish as AD advances. For moderate to severe AD, memantine is often used. It regulates glutamate activity—a neurotransmitter involved in memory and learning—by preventing excessive glutamate activity that can damage neurons. Memantine is frequently combined with cholinesterase inhibitors and helps reduce symptoms related to agitation and cognitive decline, though it also only manages symptoms rather than halting disease progression. Aducanumab, approved by the U.S. FDA in 2021 as a disease-modifying therapy, aims to reduce beta-amyloid plaques in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. However, its approval has been controversial due to mixed trial results and limited clinical benefits reported, and it remains unavailable in India and many other countries.

Non-pharmacological interventions are crucial in managing AD symptoms and improving quality of life, particularly in resource-limited settings like India where access to pharmacological treatments may be restricted. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST), involving structured activities like problem-solving and memory tasks, has been shown to improve cognitive function and delay decline in people with mild to moderate AD. Adapted cognitive stimulation programs in India have demonstrated improvements in cognitive function and quality of life. Physical exercise is another vital intervention, promoting brain health by enhancing blood flow, reducing inflammation, and releasing neurotrophic factors that support neuron survival. A balanced diet rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids, alongside mental stimulation through activities like reading and puzzles, also supports cognitive health. Caregiver education and support are particularly important in India, where family members often serve as primary caregivers. Education programs help caregivers understand AD progression, develop coping strategies, and manage stress, ultimately reducing burnout and enhancing patient care. India’s traditional Ayurvedic medicine explores alternative treatments for Alzheimer’s. Herbs such as Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) and Ashwagandha (Withaniasomnifera) have shown neuroprotective potential in early studies, with Brahmi believed to enhance memory and Ashwagandha thought to reduce oxidative stress. Despite promising results, these alternative treatments lack large-scale clinical validation and should not replace evidence-based pharmacological or non-pharmacological approaches until further research confirms their efficacy and safety.

Challenges in India

Managing Alzheimer’s disease in India presents several significant challenges, despite advances in conventional and alternative treatments. One of the primary issues is limited access to specialized care. The country has a severe shortage of dementia specialists and geriatric care providers, especially in rural regions like Kashmir. This lack of expertise leads to delayed diagnoses and inadequate management of Alzheimer’s in underserved areas. The high costs of medications, diagnostic tests, and ongoing care also pose a financial burden for many families. Basic diagnostic tools like MRI and CT scans are often limited to urban centres, making them both geographically and financially inaccessible for rural populations. Public awareness about Alzheimer’s remains low, leading to widespread misconceptions where symptoms are often dismissed as normal ageing rather than recognized as a serious condition. The stigma associated with cognitive decline further discourages early medical intervention. Additionally, caregivers, who usually carry the full responsibility of care in the absence of formal support systems, experience considerable physical, emotional, and financial strain. While new treatments, such as aducanumab, have emerged, their availability in India is limited, and their high cost makes them out of reach for most patients.

Current Research

Research into Alzheimer’s disease is advancing globally, including in India. New disease-modifying therapies, such as anti-amyloid antibodies like Lecanemab, show promise in slowing cognitive decline by targeting the disease’s underlying pathology. Tau-targeted therapies, which aim to prevent tau protein tangles associated with Alzheimer’s, are also emerging. Combination therapies, pairing anti-amyloid antibodies with BACE inhibitors, have shown encouraging results. Precision medicine-tailoring treatments to individual genetic profiles, also holds potential for diverse populations like India’s, offering hope for more effective treatments across the nation.Non-pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive training, physical exercise, and lifestyle modifications, are being explored and have been shown to delay cognitive decline in at-risk individuals. These approaches, combined with traditional pharmacological treatments, are helping to shape a more comprehensive care model for Alzheimer’s disease.

For caregivers, several evidence-based strategies can help manage the significant challenges of care. Education about the disease and its progression is essential to reducing caregiver stress and improving patient outcomes. Establishing consistent daily routines minimizes confusion and agitation for patients, while home modifications enhance safety, preventing accidents and wandering. Effective communication is key—using simple language, maintaining eye contact, and providing emotional support can improve the patient-caregiver relationship. Caregivers are also encouraged to seek support from local or online caregiver groups, practice self-care, and prioritize their mental and physical well-being to prevent burnout, which is common when dealing with Alzheimer’s patients.

Public awareness about Alzheimer’s disease remains low in many parts of India, and this is especially true in Kashmir. The region faces unique challenges, as misconceptions and stigma around Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline are widespread. This often delays diagnosis and proper treatment. Kashmir, like other rural areas in India, also suffers from a lack of specialized healthcare professionals, particularly geriatric experts. The shortage of geriatric care in Kashmir exacerbates the struggle for timely and accurate diagnosis, making it even more difficult for families to manage Alzheimer’s disease effectively.Telemedicine offers a lifeline in regions like Kashmir, where access to specialized care is severely limited. With a scarcity of geriatric experts in the region, platforms such as Teleprac are helping to bridge the gap. Through telemedicine, patients and their families can consult with geriatric specialists from reputed institutions across India, receiving critical guidance on managing the disease and accessing advanced treatment options. This remote access to expertise is vital for ensuring that even those in rural or underserved areas can receive timely care and support, significantly improving patient outcomes and easing the burden on caregivers.

Raising awareness about Alzheimer’s disease is not just about breaking the stigma—it is about transforming the way care is delivered across India, including regions like Kashmir. Public awareness campaigns can promote earlier diagnoses, reduce misconceptions, and drive policy changes that include dementia care in national health programs. Increased awareness also has the potential to attract more research funding, which is essential for tackling the unique challenges posed by Alzheimer’s in diverse regions. With the help of telemedicine and ongoing efforts to enhance both conventional and alternative treatments, there is hope for a better future for Alzheimer’s patients and their families in India.

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease presents substantial challenges to India’s healthcare system, particularly in rural areas like Kashmir, where healthcare facilities are limited. However, ongoing research, caregiver support, and awareness initiatives offer hope for improving the diagnosis, treatment, and management of the disease. Telemedicine can play a crucial role in this effort, allowing patients from Kashmir to consult with geriatric experts from reputed institutions across India without needing to travel. This ensures timely access to specialized care and guidance, regardless of geographic location.By promoting collaboration among healthcare professionals, policymakers, researchers, and the community, India can continue to enhance the management of Alzheimer’s disease, ultimately improving the quality of life for those affected. To all patients battling Alzheimer’s, please know that the scientific community is deeply dedicated to advancing research and developing new treatments with you in mind. Your courage and resilience inspire our work, and we remain committed to finding solutions that will make a difference in your lives.

To the caregivers who provide unwavering support and love, your dedication is truly admirable. Your efforts have an immeasurable impact on the lives of those you care for, and your resilience is a source of inspiration. I deeply appreciate all that you do and we are grateful for your continued commitment to improving the lives of those affected by Alzheimer’s disease.

(Dr Nawab John Dar is a post-doctoral scientist at the Salk Institute in San Diego, California. His research primarily focuses on neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. He investigates the role of iron accumulation and oxytosis/ferroptosis in the pathogenesis of these diseases. Dr Dar has made significant contributions to understanding the mechanisms underlying oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. His work aims to develop therapeutic strategies to combat these conditions. He is also the founder of Teleprac Healthcare, which strives to bridge the gap in healthcare access by offering teleconsultations with specialists, making expert care more accessible to patients, especially in Kashmir.)