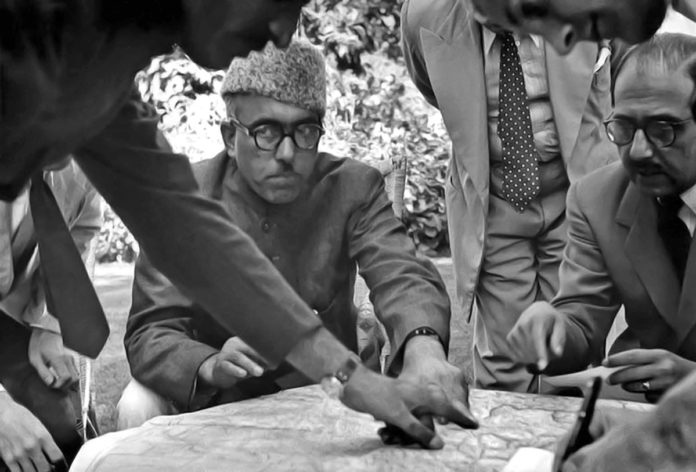

Regardless of missteps, reversals, and controversial compromises, Sheikh Abdullah shaped the political evolution and consciousness of Kashmir over his 50-year career, writes Muhammad Nadeem after going through Altaf Hussain Para’s political biography of the towering Kashmir leader

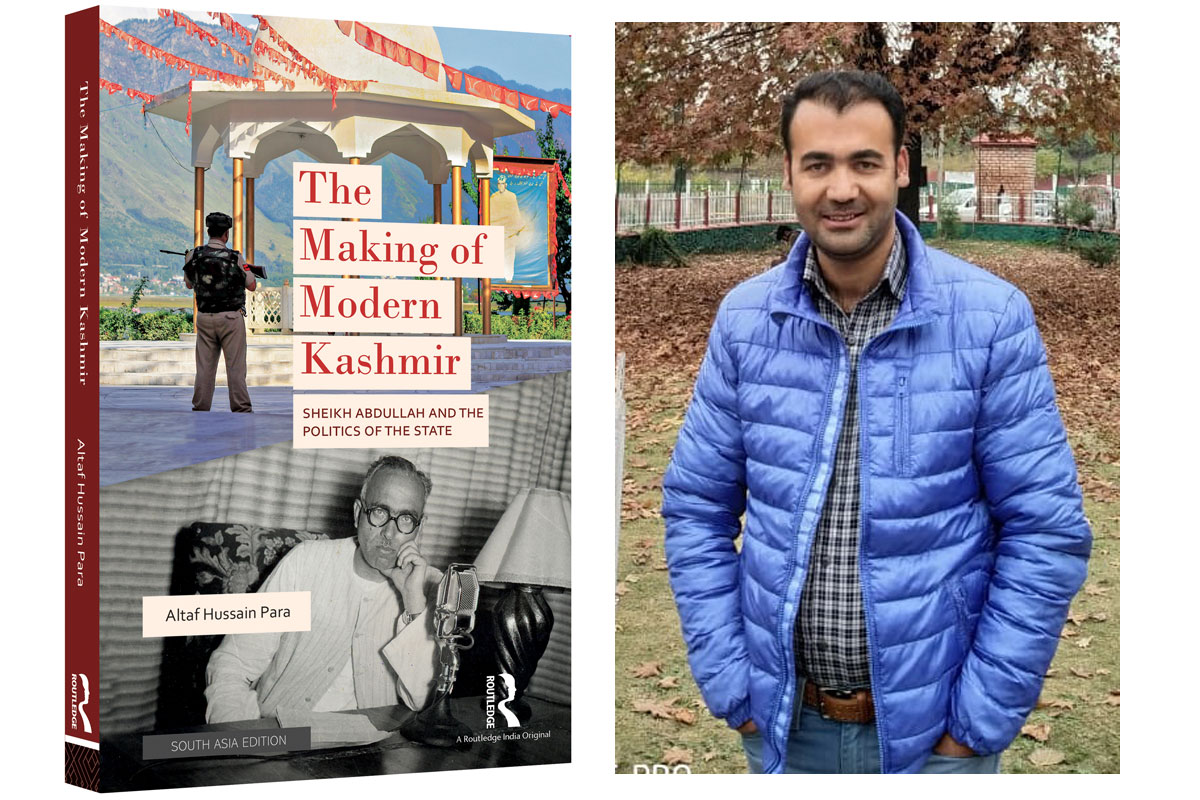

In The Making of Modern Kashmir: Sheikh Abdullah and the Politics of the State, Altaf Hussain Para presents a comprehensive political biography of Sheikh Abdullah (1905-1982), examining his central role in shaping the politics of Kashmir in the 20th century. Situated within the academic fields of South Asian history and politics, the book traces Abdullah’s rise from a young anti-colonial activist in the 1930s to his eventual status as the preeminent leader of Kashmir over the next five decades. Para analyses Abdullah’s complex and often contradictory political career through the lens of state formation, popular mobilisation, competing nationalist projects, and the dynamics between regional politics and Indian federalism.

The book highlights the divergent perspectives on Abdullah within existing scholarship, which Para notes range from viewing him as a “tragic hero” to accusations against him of betraying Kashmir’s political aspirations. Para engages with pioneering texts on Kashmir by scholars as well as more recent journalistic accounts. However, the author identifies the lack of rigorous attention devoted to Abdullah’s political career and ideology as a significant gap, which this book aims to address through research into original archival material and interviews.

A Multilayered Analysis

Para combines archival research to construct a multilayered analysis of Abdullah’s political trajectory. The author analyses Abdullah’s role during key events, from his initial emergence in the 1931 anti-monarchical agitation through to the Plebiscite Movement, explorations of third-party mediation, and final reconciliation with Indira Gandhi’s government in 1975. Para evaluates Abdullah as a complex historical subject, avoiding simplistic hagiography or vilification. It elucidates Abdullah’s changing ideological perspectives and situates his decisions within the swirling political forces operating in Kashmir.

The central question guiding Para’s analysis is: What was Sheikh Abdullah’s contribution to making modern Kashmir, and what enduring political legacy did he leave behind? Para argues that Abdullah was the chief architect of modern Kashmir, spearheading the transformation of the state from a feudal princely entity into a modernising postcolonial state, while also embedding the unresolved issue of Kashmir’s political status within India. The book’s underlying thesis is that despite his blunders and political reversals, Abdullah shaped Kashmir’s transition towards mass politics and nationalism.

The diverse array of data sources is one of the book’s major strengths. Para marshals private diaries, political pamphlets, government archival records, newspaper reports, published memoirs, and extensive firsthand interviews into a compelling evidence base. Such comprehensive sourcing enables a nuanced assessment of how Abdullah navigated complex political developments from multiple vantage points. From nationalist poetry lionising Abdullah as Kashmir’s saviour to conflicting portrayals of his stance on Kashmir’s accession to India, Para evaluates the veracity and context behind the various sources, lending credibility to his analysis.

The book employs Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony to theoretically contextualise Abdullah’s ascendence as Kashmir’s preeminent political leader through cultivated mass consent rather than coercive force. Para utilises this framework to underscore how Abdullah channelled Kashmiris’ frustrations against despotic rule by becoming the voice of the oppressed masses, enabling his rise from schoolteacher to Lion of Kashmir. However, Para avoids excessive extrapolation of Gramsci’s theoretical concepts, not forcing history to fit abstract models. His analysis prioritises revealing the on-the-ground complexities of Abdullah’s leadership.

Dispassionate Analysis

Para constructs his arguments with attention to historical detail and cautious analysis, avoiding judgmental interpretations. For instance, in examining the origins of Abdullah’s grievances with the region’s Dogra rulers, Para does not portray communal discrimination as the sole factor.

Instead, he situates Abdullah’s ideological development at the nexus of the stifling lack of socioeconomic mobility, Kashmir’s fractured modernity under a feudal autocracy, and inspiration from anticolonial movements in British India. Para’s chronological structure centres Abdullah as the connecting thread across the tumultuous events that moulded modern Kashmiri political identity.

A History of Resistance

Sheikh Abdullah’s political journey, spanning from 1953 when he was ousted as the Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir until the early 1970s when he reached an accord with the government of India, is a narrative that chronicles his persistent resistance against the escalating integration of Jammu and Kashmir into the Indian Union during this period.

Abdullah’s dismissal in 1953 by Nehru’s government and subsequent arrest, triggered mass protests in Kashmir. The establishment of the Plebiscite Front in 1955, advocated for self-determination for Kashmiris. Abdullah’s release from prison in 1958 and his vigorous campaign for a plebiscite, resulted in his rearrest that same year. The theft of the Holy Relic from the Hazratbal shrine in 1963, sparked protests and calls for Abdullah’s release.

The author tries to deconstruct Abdullah’s release in 1964, his discussions with Nehru about Kashmir’s status, and Nehru’s subsequent demise, India’s progressive erosion of Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy prompted protests by Abdullah and the Plebiscite Front, the Indo-Pak War of 1965 and the uprising in Kashmir, Abdullah’s increasing willingness, starting in 1968, to entertain compromises with India, and eventually, his agreement with Indira Gandhi in 1974, and how it reaffirmed Kashmir’s incorporation into India.

Sheikh Abdullah’s political struggles spanning two decades against India’s integrationist Kashmir policy underscore how his dismissal and arrest in 1953 transformed him into a symbol of Kashmiri nationalist aspirations, providing a blow-by-blow account of the complex dynamics and evolving positions in this protracted political saga.

The Accord

The Kashmir Accord of 1975, a pivotal agreement between Sheikh Abdullah and Indira Gandhi, marked the culmination of a reconciliation process initiated in 1968. This accord formally concluded Abdullah’s two-decade-long political struggle for Kashmir’s permanent autonomous status. However, it was met with scepticism by many Kashmiris who perceived it as a betrayal.

The accord affirmed Jammu and Kashmir as a constituent unit of India, subject to governance under Article 370. It granted the state government limited powers to review central laws extended after 1953. Nevertheless, it acknowledged the erosion of autonomy since 1953 rather than reinstating the pre-1953 constitutional provisions, as Abdullah had initially demanded.

Tied to political arrangements, the accord involved the dissolution of the Plebiscite Front and the Congress relinquishing power to facilitate Abdullah’s return as Chief Minister. This quest for power, after a prolonged exile, tarnished Abdullah’s image as an unwavering mass leader.

During his second term as Chief Minister (1975-1982), Abdullah failed to restore autonomy, resolve the Kashmir issue, or establish a sustainable secular, social democratic political framework. Resorting to authoritarian measures, he imprisoned opponents and stifled dissent.

Regional tensions surfaced through agitations in Jammu and Ladakh, which Abdullah dismissively threatened to separate from Kashmir rather than accommodate. His regime witnessed growing discontent and communal polarization.

Abdullah’s compromise on self-determination and autonomy led to a loss of credibility, especially among the youth. His appointment of his inexperienced son as a successor and engagement in dynasty politics further harmed his image. The 1975 accord is perceived as a significant betrayal that shattered Kashmiri’s trust in leadership.

A ‘Visionary’ Leadership

Para guides readers through the intricate tapestry of events enmeshing Kashmir’s contentious modern political history with Abdullah’s ‘visionary’ yet flawed leadership. Avoiding dense academic prose, his approach facilitates contextualising Abdullah’s decisions and shifting stances in response to changing realities on the ground. Para employs interview material to illustrate how ordinary Kashmiris perceived Abdullah, often washing away his grave mistakes out of unwavering popular loyalty. This book represents an invaluable resource for both scholars studying modern South Asian history and politics as well as policy practitioners seeking to understand the complex origins of the Kashmir issue’s intractability.

Para’s elucidation of how competing nationalist visions collided in Kashmir’s over-determined control of the state’s destiny provides a critical historical context for why contemporary peace remains so elusive and divisive. Para’s sources are properly cited throughout using the Chicago style formatting typical of historical scholarship. The diversity of references demonstrates the book’s foundations in multi-year research efforts synthesizing an expansive range of resources.

A Political Biography

The book’s foremost contribution lies in providing the first full-length scholarly political biography focused exclusively on unpacking the figure of Sheikh Abdullah. Para advances understanding of Abdullah’s ideological evolution from his early rejection of Kashmir’s feudal order towards his later accommodations with India, supplemented by analytical insights into how India’s ruling Congress Party alternatively tried co-opting or suppressing him at different junctures. Besides, the study maps Abdullah’s enduring imprint upon Kashmir’s political landscape for decades through the successive regional protégés he mentored.

Within the constraints of political biography, Para offers a critique of how unfulfilled promises on autonomy and democratic institutions heightened disenchantment with India among Kashmiris and laid the seeds for future unrest.

Conclusion

In the tumultuous crucible of Kashmir’s nationalist awakening against despotism, Sheikh Abdullah rose as a figure able to mobilise mass support, becoming etched in popular memory even after surviving his frequent ideological swings. As Para highlights, despite missteps, reversals, and controversial compromises, Abdullah shaped the political evolution and consciousness of Kashmir over his 50-year career, though the ramifications still linger today.

By documenting Abdullah’s multi-faceted leadership of Kashmir’s nationalist movement, this book contributes to the state’s complex modern history and current status. Para’s comprehensive analysis expands established historiography, elucidating through the lens of Abdullah’s eventful life the dialectic forces that moulded Kashmir into its present form.